Bumblebees (Figure 1) are prone to catch your attention with their sonicating buzz or conspicuous and colorful appearance. They are robust, fuzzy-looking insects, with varying bands of coloration and a hairy abdomen. This characteristic differentiates them from the look-alike carpenter bees. Carpenter bees have bald abdomens. Similar to honeybees, bumblebees are in the family Apidae; they are social bees but survive or just one season, unlike honeybees. Bumblebees usually are active from early spring through fall, visiting and collecting pollen and nectar from flowers.

Photo: Joshua Fuder, University of Georgia.

Bumblebees are distributed worldwide, with up to 260 species all over the globe. Most species are encountered in the Northern Hemisphere, while others are located in Central and South America and northern Africa. Forty-nine bumblebee species in the United States are known, and 17 of them are found in Georgia. Bombus impatiens (Figure 2) is the most common bumblebee species in Georgia. The size of individual bumblebees varies across species and castes. Broadly, there are three castes: queen, workers, and drones. The queen bumblebee can vary from 17–25 mm in length; the male drones range from 13–23 mm, while the female workers are considerably smaller than the queen and range from 10–20 mm.

Photos: (A) David Cappaert, Bugwood.org and (B) Shimat V. Joseph, University of Georgia.

Bumblebees are greatly valued as pollinators of native and nonnative plants, including ornamentals and cultivated plants such as blueberries. Because of their body morphology and behavior, bumblebees are particularly efficient in pollinating certain economically important crops, such as tomatoes, cranberries, cucumbers, and watermelons. Certain bumblebee species are sold to greenhouses for their pollination services with a value of up to $10 billion USD annually. Additionally, the decline in bumblebee populations has been widely reported worldwide, where agricultural intensification, habitat loss, increased use of pesticides, and microsporidian pathogen Nosema bombi are implicated in bumblebee decline. Many species of bees that were once found in certain areas are now reportedly missing and have not been encountered in the past 10–15 years. For example, Bombus pensylvanicus and Bombus affinis (Figure 3) are native bumblebees to Georgia that are now considered threatened or at risk of population decline.

Photos: (A) B. Merle Shepard, Clemson University, Bugwood.org, and (B) Johanna James-Heinz, https://bugguide.net/node/view/240914.

Description

Bumblebees generally are large bees with black and yellow hairs all over their bodies. They can be distinguished from other bee species by the pollen basket (corbicula) on the female’s hind legs, which is usually flattened, concave, and with hairs only around the outer edges. Honeybees also have pollen baskets.

Biology

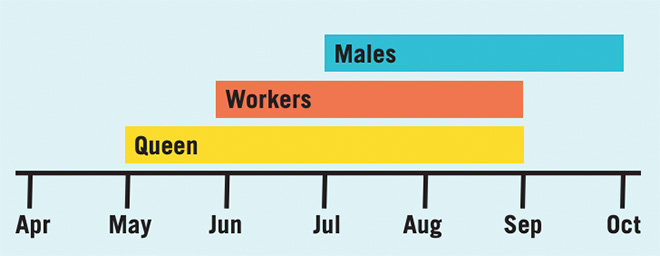

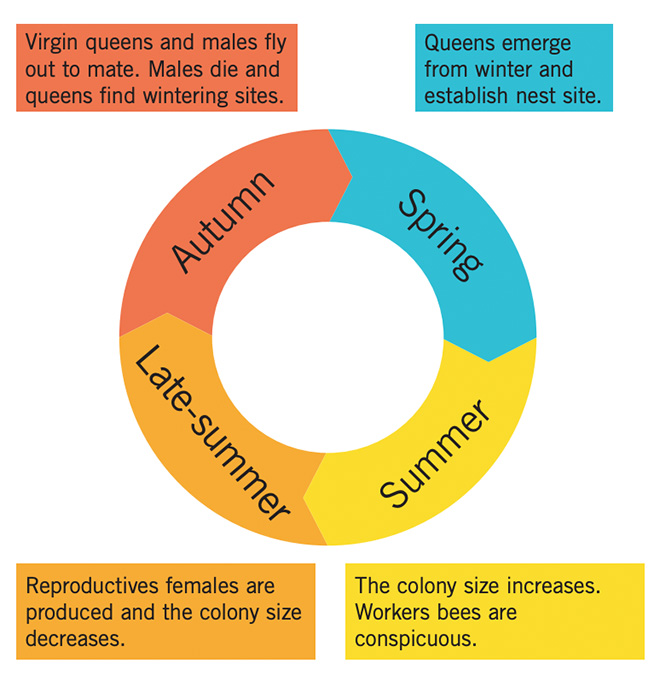

Bumblebees are social insects with individuals responsible for performing specific functions for colony survival. The workers and males (drones) in the bumblebee colony die at the end of the summer, except for the newly mated and overwintering queen (Figure 4). In spring, the overwintered queen seeks out a new nesting site and begins a new colony.

Adapted from ”Bumblebees of the Eastern United States,” by S. Colla, L.L. Richardson, and P.H. Williams, 2011, United States Forest Service, United States Department of Agriculture (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259460463_Bumblebees_of_the_eastern_United_States).

Each bumblebee colony maintains a relatively constant nest temperature regardless of the ambient temperature. They generate heat in their bodies by shaking their flight muscles, enabling them to be active in the wet and cool mornings of spring. Bumblebees do not build their own nests but utilize abandoned rodent burrows, hollow logs, and open grass tussocks as nesting sites. Once a suitable nest is determined (Figure 5), the overwintering queen gathers pollen and builds a wax honeypot (Figure 6) for nectar storage. She lays a cluster of eggs (8–14 eggs per cluster) on a pollen ball and covers the eggs up with a waxy pot called the brood clump.

Photo: Joshua Fuder, University of Georgia.

Photos: (A) Ian Burns, University of Minnesota, and (B) Clare Flynn, https://www.bumblebeeconservation.org/bumblebee-nests/.

Two weeks after eggs are laid, the larvae hatch and feed on the pollen ball (Figure 7). The queen shuffles between incubating the larvae and collecting pollen during this stage. The larvae feed for about 2 weeks and then form a cocoon, where they spend the pupal stage (for another 2 weeks) to emerge as bumblebee workers. These newly emerged female worker bees will take on foraging for resources, tending eggs and larvae, regulating the nest temperature, and defending the nest. The queen remains in the nest and continues to lay eggs (oviposit), increasing the colony’s size. Toward the end of the summer, the queen begins to produce males and reproductive females (queens) that will begin new colonies the following year. The new queen may mate with only one male or with several males, mixing the sperm in a storage organ called the spermatheca. Then she will feed to build fat reserves that will sustain her through overwintering. By late fall, the colony dies, as they cannot withstand the adverse weather conditions. The new queens, however, survive and burrow into the ground, remaining inactive until the following spring.

Ecology and Conservation

Bumblebees are important pollinators of many plants in landscapes and specialty crops. They forage and pollinate many wildflowers and native plants, maintaining diversity in native plant communities as they coevolve with certain native plants. They are floral generalists capable of utilizing many flower species, although they mostly focus on one plant genus in a foraging flight. Bumblebees collect pollen from certain plants by vigorously vibrating their flight muscles to release pollen from the anthers, which is also referred to as buzz pollination. Economically important crops that benefit from buzz pollinations are tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum), eggplants (Solanum melongena), cucumbers (Cucumis sativus), potatoes (Solanum tuberosum), cranberries (Vaccinium spp.), blueberries (Vaccinium spp.), squash (Cucurbita spp.), alfalfa (Medicago sativa), and clover (Trifolium spp.).

The economic value of bumblebees as efficient pollinators has increased over the years as many greenhouse production operations purchase them for their services. However, commercially produced bumblebees also have been implicated in spreading pathogens to existing native bumblebee popoulations, causing serious diseases. Bumblebees interact with several plants by obtaining their nutrition from pollen and nectar. New queens visit pollen and nectar-rich flowers in early spring to build their energy stores before building the colony. The pollen provides the much needed for the growth of young larvae in bee pots. To sustain bumblebee colonies, readily available nutritional resources are a must. Bumblebee populations face numersous challenges such as increased pesticide use, habitat loss or fragmentation, climate change, diseases, and natural enemies. To reduce habitat fragmentation, land should be managed carefully so that there are minimal effects on bumblebee colonies. Consider developing more nesting habitats, such as planting tall grass strips and providing wildflower landscapes to promote colony survival and success.

References

Cameron, S. A., Dozier, J. D., Strange, J. P., Koch, J. B., Cordes, N., Solter, L. F., & Griswold, T. L. (2011). Patterns of widespread decline in North American bumble bees. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, 108(2). https://www.pnas.org/doi/ full/10.1073/pnas.1014743108

Carril, O. M., & Wilson, J. S. (2021). Bombus. In Common bees of eastern North America. Princeton University Press. https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691218694/common-bees-of-eastern-north-america

Colla, S., Richardson, L. L., & Williams, P. H. (2011). Bumblebees of the eastern United States. United States Forest Service, United States Department of Agriculture. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259460463_Bumblebees_of_the_eastern_United_States

Gratton Lab. (2021). Bumble bee declines. Bumble Bees of Wisconsin. https://wisconsinbumblebees.entomology.wisc.edu/ about-bumble-bees/bumble-bee-declines/

Mitchell, T. B. (1962). Bees of the eastern United States, Vol. II (Technical Bulletin No. 152). North Carolina Agricultural Experiment Station.

Morse, D. H. (1982). Behavior and ecology of bumble bees. In H. R. Hermann (Ed.), Social Insects, Vol. 3 (pp. 245–322), Chapter 2. Academic Press. https://shop.elsevier.com/books/social-insects-v3/hermani/978-0-12-342203-3

Stange, L. A., & Fasulo, T. R. (1998). Bees of Florida. University of Florida IFAS Extension. https://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/misc/bees/bumble_bees.htm

Williams, P. H., Thorp, R. W., Richardson, L. L., & Colla, S. R. (2014). Bumblebees of North America: an identification guide (pp 7—37). Princeton University Press. https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691152226/bumble-bees-of-north-america

Status and Revision History

Published on Aug 17, 2023