Author: Dennis Brothers, Associate Extension Professor, Auburn University, Agricultural Economics and Rural Sociology

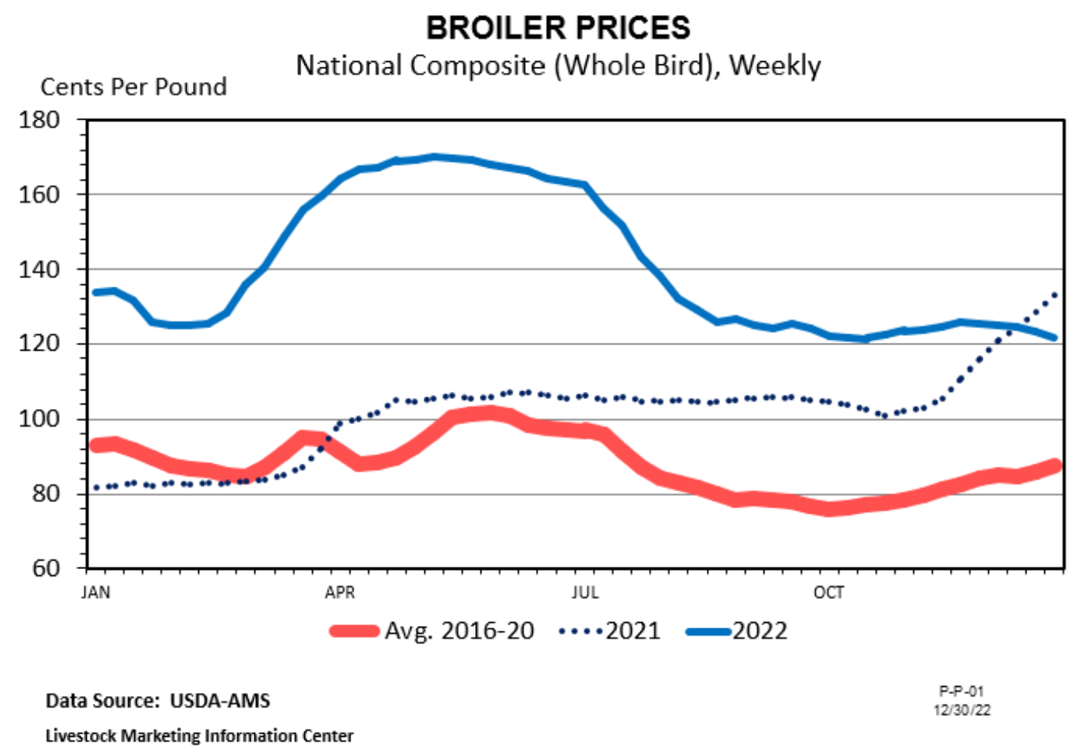

Despite continued high feed prices, commercial poultry companies have had a good year in 2022. The composite, or average price, for chicken has currently stabilized down from record levels but may stay high well into the spring of 2023. Sustained inflationary pressure and the continued talk of recession, combined with the higher prices of beef and pork will continue to push consumers toward chicken, shoring up demand.

Responding to the high demand and price, companies are striving to provide a strong supply of chicken. For the most part it seems they are succeeding—production has ramped up and an ample quantity of chicken can be found on most store shelves. These efforts should help moderate prices if the supply chain stays intact. Rail-transport labor troubles could send a shockwave throughout the poultry industry, and indeed the protein industry overall, as a high percentage of feed ingredients are transported via rail.

Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) remains a top concern for commercial poultry. The commercial egg and turkey sectors have suffered the most in 2022. Losses this year have now exceeded the previous high of 5.4 million total head from 2015. A late reported outbreak in a Southeastern commercial breeder flock is concerning for the “broiler belt” going into the winter. Further breaks in broiler operations, particularly in dense production areas, could disrupt domestic supply and give export customers a reason to disallow U.S. chicken into their overseas markets, stifling a currently robust trade market.

HPAI’s impact on the table egg markets has been substantial. Table egg prices started the year at slightly above 2021 at $1.00 per dozen and ended the year just above $4.00 per dozen. HPAI’s continued presence may help keep prices up and supply tight. Table egg demand has been above baseline for the last half of 2022, while eggs processed have been below 2021 for the same period. The Supreme Court case concerning California’s Proposition 12 ruling could have significant implications going forward as producers’ ability to market traditional caged layer eggs could be impacted.

Hindering the efforts to expand production is the ever-increasing cost of new housing combined with increasing interest rates. It is becoming almost impossible for new growers to secure financing for new farms without heavy cash incentives from integrators combined with governmental loan guarantees. It is questionable whether integrators can sustain housing incentives long-term. One growing trend is investment capital groups building and/or purchasing large farms with large numbers of houses and operating them using hired management and labor. This model bypasses the equity problem and gets chickens to the plant, but represents a departure from the traditional family-farm model that has been the staple of the contract poultry farm. The long-term outlook is unknown for such operations, and it is unknown whether these groups will retain ownership and continue to operate the farms past the depreciation period.

For growers, the recent merger of Wayne-Sanderson under the Cargill umbrella holds particular interest. As part of the Federal Trade Commission’s ruling, spurred by a lawsuit by the Department of Justice filed in July 2022, the competitive pay system (also known as “tournament pay”) was disallowed and Wayne-Sanderson was directed to modify the pay system for broiler growers. They may follow the patterns of other companies that have already modified their grower pay. One such new pay system sets a base pay per pound of delivered birds to the plant and allows for small increases based on performance resulting in several thousand dollars of potential increase in pay per flock. Another system guarantees a percentage of the total pay on a square-foot basis, while leaving a significant portion as a performance-based bonus paid per pound of birds delivered to the plant. The main difference in these systems from the traditional tournament system is that most of a grower’s pay does not change regardless of their individual performance or live cost.

The new Wayne-Sanderson has complexes that overlap with other integrators where competition for growers exists. It could be expected that if a new payment program proves successful, other integrators may be forced to change their pay programs to compete for growers. For growers considering such opportunities, they must look at not only their current revenues but also at what the potential pay programs would allow or guarantee. Depending on where the new pay falls in comparison to what is possible under their current system, growers historically receiving better-than-average tournament pay may experience a decline in revenue. Figure 1 illustrates how performance pay incentives can have significant impact on a farm’s net income. I would not expect guaranteed per-pound pay rates to be set very close to the highest pay rates possible in most traditional tournament systems.

| Broiler Farm Income Estimates (2 - 66 ft x 600 ft) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Expense/Income | Farm A | Farm B |

| Total square footage | 72,000 | 72,000 |

| Gross revenue per square foot ($ per lb annualized) | $2.75 | $3.25 |

| Gross revenue | $198,000.00 | $234,000.00 |

| Variable expenses | ($69,300.00) | ($58,500.00) |

| Income before debt service | $128,700.00 | $175,500.00 |

| Debt service assignment (50%) | ($99,000.00) | ($117,000.00) |

| Annual net farm income (ANFI) | $29,700.00 | $58,500.00 |

| ANFI per square foot | $0.71 | $1.39 |

| Note. Farm A and B represent two scenarios for broiler farms with a $28,800 total increase in annual farm income for Farm B. Only $10,800 of that increase is from lower expenses, or “efficiency” improvements. The other $18,000 (62%) in additional income is the result of performance pay, both in increased pay rate and increased pounds. According to where a guaranteed pay rate falls, this total revenue increase seen in Farm B may or may not be available to a grower in a noncompetitive pay system. | ||

There has been some discussion of broiler growers wanting to be paid on a simple per-square-foot basis without a production component or performance incentive (resembling contract-breeder pullet pay). While this would solidify a more consistent revenue for growers, one concern is companies could increase bird placement and weights and decrease downtimes, thus maximizing pounds per square foot during favorable markets without necessarily having to increase pay for growers. However, as pounds per square foot increase through the houses, expenses increase for the grower. Without a production component based on pounds going out the chicken-house door, growers easily could get the short end of such a deal. Having at least some of their income based on pounds delivered is the only way to ensure any increased expenses related to production increases could be offset. At the same time, integrators have some concern that setting a constant base pay without production incentives could breed complacency among the growers, and consequently increase overall live cost to the company through resulting inefficiencies. Some mixture of pay per square foot combined with some pay per pound could help offset these concerns.

Status and Revision History

Published on Aug 28, 2023