Mole crickets are serious pests of Georgia turf. Estimates of mole cricket losses in commercial, recreational and residential sod now exceed $20 million annually. Weather and soil conditions in Georgia’s Coastal Plain region are ideal for mole crickets, and damage continues to increase.

Georgia has three species of mole crickets. The northern mole cricket, Neocurtila hexadactyla, is native and of little economic importance. Two pest species — the tawny mole cricket (Scapteriscus vicinus) and the southern mole cricket (Scapteriscus borellii) — were introduced into the United States at the port of Brunswick, Georgia, in the ballasts of merchant ships from South America in the early 1900s. From the first introductions and others made at ports in the southern United States, mole crickets now infest sod throughout the southeastern Coastal Plain from Texas to North Carolina.

Biology

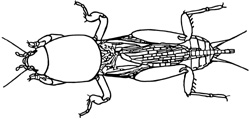

Adult and nymphal mole crickets showing size difference.

Adult and nymphal mole crickets showing size difference.Mole crickets spend the winter deep in the soil predominantly as adults and large nymphs. Those that overwinter as nymphs complete their development and become adults in the spring in time for mating season. Mating takes place in late winter and early spring as soil and air temperatures warm. Males construct special chambers at the surface end of their tunnels and produce a call or song that attracts females. Both males and females fly on warm, humid nights, sometimes in huge numbers, looking for mates or new areas to lay their eggs. The peak of tawny mole cricket flight activity is March and early April. Southern mole cricket flight peaks in April and early May, with some individuals flying on humid nights through June.

Approximately 14 days after mating, the female constructs an egg chamber 6 to 18 inches deep in the soil (depending on soil type, moisture and temperature) and lays an average of 35 to 40 eggs. A single female can lay several clutches and has the potential to produce more than 100 offspring. Adults of both sexes die after mating and reproductive season, and few adult mole crickets remain after June.

Eggs take 3 to 4 weeks to hatch, depending on temperature. In Georgia, most eggs hatch in late May or early June, although some southern mole crickets hatch as late as August. Newly-hatched nymphs resemble adults but are smaller and lack wings. They begin to feed and tunnel immediately after hatching. Nymphal mole crickets molt 8 to 10 times in the 3 or 4 months it takes them to become adults. Adult mole crickets spend late fall and winter in the soil, feeding during warm periods and waiting for spring.

Damage

Mole crickets damage turf by feeding on the plant roots, stems and leaves, and by tunneling through the soil. Mole cricket feeding is not considered as damaging as their tunneling. Significant feeding injury does occur in pasture and forage systems, but the extensive tunneling is most often associated with mole cricket damage in turf.

Mole crickets in turf.

Mole crickets in turf.The size and extent of tunneling increases as the mole cricket ages. Early instar nymphs may live in an area of only a few square feet and cause very little noticeable damage. It is not uncommon to find 5 to 10 first-instar mole cricket nymphs per square foot with little or no injury to the turf. In summer or early fall, however, larger nymphs may tunnel over an area of several yards and cause extensive injury. It is, therefore, impossible to develop a threshold for treatment based only on the number of mole crickets per unit area.

The size of tunnels can be used to indicate the age of an existing mole cricket population. Many golf course superintendents examine sand traps for mole cricket tunnels to determine when the spring hatch begins. As the mole cricket increases in size, so does the tunnel.

Control

Mole cricket control is a continuous problem for homeowners, turfgrass managers and sod producers in the Coastal Plain area of Georgia. An effective program requires keeping close tabs on the mole cricket population and matching control efforts to local conditions, the life cycle of the pests, and demands on the turf. Distinctly different strategies are appropriate for spring (March-May), summer (June-September) and fall.

Spring Treatments

In the spring, almost all mole crickets are in the adult stage. They are very active during warm periods and cause considerable tunneling and feeding damage. This is also the time of maximum flight activity and dispersal, a time when areas free of mole crickets can become infested. The crickets are sensitive to local weather conditions, especially early in the spring, and may retreat underground for extended periods if the weather turns cold or wet.

This combination of large crickets, unpredictable weather, pest activity and frequent large dispersal flights makes control of mole crickets in spring difficult. Weather and cricket activity are more predictable in late April and May, but by then, a significant number of mole cricket eggs may already have been laid, and these eggs are not affected by insecticide treatments. Logically, there should be a window of time after most of the flight is over and before egg laying when treatments would be effective at reducing adult populations as well as controlling the next generation. In practice, however, this has not worked.

Sod producers with mole cricket problems in the spring should treat only those areas where damage is severe and where sod will be cut early in the season before the grass has a chance to recover. Other turf managers should treat only the areas where damage is so severe that grass is being lost. This is a spot treatment approach, and baits may be the best option. Where damage is less severe, note the location of adult activity and target those areas for treatment after eggs hatch.

Summer Treatments

The nymph population increases throughout June and, by July, almost all eggs that are going to hatch will have done so. At the same time, the adults begin to die off and very few will be flying. (Those that do fly are mostly southern mole crickets and are unlikely to do much damage except in critical areas like golf greens and tees.) While time of peak egg hatch will vary from year to year, precise timing of control efforts is not necessary. Newly hatched nymphs are so small they do almost no damage and are very difficult to detect. Delaying application until late June ensures that all of the current generation will have hatched. These small nymphs spend more time at or near the surface than do larger nymphs and are relatively easy to kill.

This is the ideal time to treat for mole crickets. (If you have nematode problems, delay treatment until this time in order to treat both problems with one pesticide application.) Almost any of the routinely recommended materials will provide good control of young crickets. As summer goes on and the crickets grow, activity and damage increase and the crickets become harder to kill. By late August or early September, control may be difficult to achieve.

Fall Treatments

Adult tawny mole crickets begin to appear in mid-September, and by late November, they comprise more than half the population. Those nymphs still present are large and active, but apparently the adults do not move around much in the fall. Activity of nymphs is affected by the weather and becomes sporadic as the season advances.

As in the spring, control can be very difficult to achieve in late fall. Treat only those areas where the damage is extensive or critical such as golf greens, high traffic areas or sod fields that will be harvested that fall or early the next season. Baits have also proven very effective on these large late-season nymphs.

Pesticide Application

Regardless of the pesticide chosen or time of application, some steps should be taken to maximize control. Remember that all pesticides are affected by heat and sunlight and that mole crickets are most active at night. Apply the insecticide as late in the day as possible to maximize these effects. (This may mean treating only part of the golf course or park on one day.) For materials that are applied as liquid solutions, apply at least 1 gallon of solution per 1,000 square feet. Unless the label instructs otherwise, irrigate thoroughly after application to move the material from the foliage and down to the soil surface.

Check the pH of your mix water and, if the pH is more than about 7.5, add a buffer to the tank to bring the pH down to the 5.5-6.5 range.

If adequate irrigation is available, the mole crickets themselves can be manipulated to increase control. Allow the soil to dry out for 3 or 4 days and then irrigate thoroughly in the evening. Apply the insecticide the next afternoon. Mole crickets are sensitive to soil moisture and will move down in the ground to find comfortable conditions if the surface is dry. Irrigation will bring them back up to resume feeding the following night, making them easier targets for control.

For current pesticide recommendations, contact your local County Cooperative Extension Office.

Status and Revision History

Published on Oct 05, 2007

Published on Sep 10, 2010

Published with Full Review on Oct 01, 2013