- Historical Background of Citrus in the United States

- Selecting Varieties

- Rootstock Selection

- Pollination

- Establishment and Care of Young Citrus

- Site Selection and Spacing

- Purchasing Trees

- Tree Selection and Planting Procedures

- Fertilization

- Cold Protection

- Cold Hardiness and Factors Affecting Freeze Damage

- Care of the Bearing Tree

- Other Cultural Problems

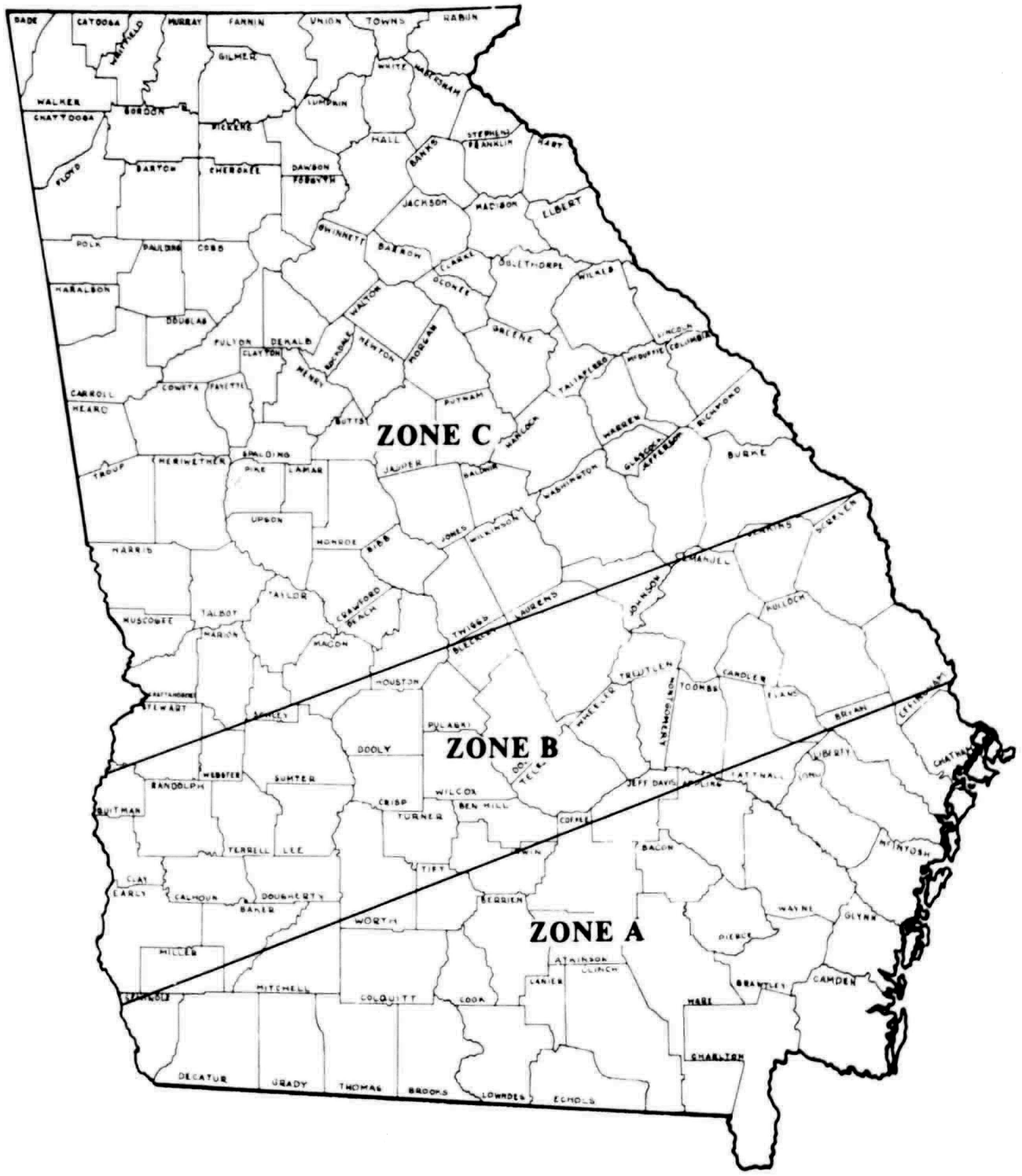

Citrus plants are very versatile around the home and may be used as individual specimens, hedges or container plants. Their natural beauty and ripe fruits make them attractive additions to the South Georgia home scene. Cold-hardy varieties that receive recommended care may grow successfully in the coastal and extreme southern areas of the state (and to a lesser degree in more northern locations). Areas where citrus are best adapted within the state are shown in Figure 1.

The most significant limiting factor to citrus culture in these areas is damage from severe winter temperature. The following brief history of citrus culture in the United States vividly illustrates the devastating effect of winter freezes.

Figure 1. Citrus is best adapted to Zone A. With adequate cold protection, cold hardy selections may be grown in Zone B with some success. Citrus can be grown in lower Zone C, but extensive cold protection measures will be needed in some years.

Figure 1. Citrus is best adapted to Zone A. With adequate cold protection, cold hardy selections may be grown in Zone B with some success. Citrus can be grown in lower Zone C, but extensive cold protection measures will be needed in some years.

Historical Background of Citrus in the U.S.

Citrus was first introduced into the continental United States by early Spanish explorers at Saint Augustine, Florida, in 1565. Considerable time elapsed before citrus was introduced into Arizona (1707) and California (1769).

History indicates that citrus plants have been grown for many years in gardens near the Gulf of Mexico and even as far north as Charleston, South Carolina. Small satsuma plantings were developed in the Gulf states as early as the 1890s but were destroyed by the freezes of 1894-95 and 1899. Plantings resumed until the freeze of 1916-17 struck, killing thousands of acres. By the early 1940s the hardy satsuma had again made a comeback, with some 12,000 acres growing in the Gulf states of Louisiana, Alabama and northern Florida. But freezes in the two decades following World War II mostly eliminated these plantings. Currently the main commercial areas are on the Gulf Coast of Louisiana, Florida, and southern Georgia.

Selecting Varieties

Sweet Types of Citrus

The three general classes of citrus that produce sweet fruits are mandarins, sweet oranges and grapefruit. All of these citrus types develop into attractive, medium- to large-size trees. However, some are better adapted to South Georgia conditions than others.

Mandarins

This citrus class includes a large group of loose-skinned, deeply-colored, highly-flavored fruits. They are sometimes referred to as the kid-glove (easily peeled) fruits. Within this group are the satsumas, tangerines, and tangerine hybrids. The terms mandarin and tangerine are used interchangeably for a number of loose-skinned fruits, depending upon where they are grown. For example Dancy is called a tangerine in Florida and a mandarin in California. Unlike other types of citrus, cross-pollination is required for optimum fruiting of a number of tangerine varieties and hybrids.

Satsuma

The highest degree of success and greatest satisfaction in growing citrus in Georgia will be realized with the satsuma. It will withstand colder temperatures, produce more consistent crops over a longer period of time and requires less cold protection than other types of sweet citrus.

The satsuma is distinctly different from other mandarins. It does not require a pollinator (it's "self-fruitful"), has excellent cold hardiness, and ripens its fruit well ahead of any freeze problems (September to November). 'Owari' is the most popular variety, and is generally available at retail outlets or online from citrus nurseries. 'Brown Select' and 'Silverhill' are other good varieties. 'Owari', 'Brown Select', and 'Silverhill' often ripen by late October. Fruits retain their peak quality for about 2 weeks, after which they may become puffy, rough in appearance, and lose flavor and juice content.

An important fact to remember when growing satsumas is that fruits become fully ripened for eating before the peel is completely orange. This is especially true of early ripening varieties. There are numerous early varieties such as 'Miho', 'Xie Shan', 'Early St. Ann', and 'LA Early'. In general, fruit from early ripening satsumas are not as good quality as varieties that ripen in November. Certain fruits will ripen ahead of others, but by beginning to harvest when the first few fruits become ripe, at least 1 to 2 weeks may be added to the length of the harvesting period.

Changhsa

Changsha is a very cold-hardy mandarin. Its juice has a higher sugar content than satsumas but are not as juicy. Most are very seedy and tend to bear heavily in alternate years (called "alternate bear"). 'SweetFrost', a variety that was developed recently by the University of Georgia, has fewer seeds. Fruit of 'SweetFrost' ripen in November and are a beautiful dark orange color. The trees have consistent production.

Dancy and Ponkan

Both Dancy and Ponkan are exceptionally good tangerine varieties that produce quality fruits. However, their fruits may not develop good flavor before early- to mid-December, so they may be exposed to freezing temperatures before attaining optimum ripeness. The Ponkan reportedly is less cold-resistant than most mandarins. Its fruits lose quality and the rind puffs if it is not picked when ripe. Earlier-ripening selections such as the Clementine (Algerian) tangerine should be planted where possible. Dancy and Ponkan are self-fruitful, but Clementine requires cross-pollination from another tangerine or tangerine hybrid. The tangerine hybrids described below provide some exceptionally good early-maturing varieties that should be of interest to the homeowner.

Tangerine Hybrids

Tangelos are tangerine-grapefruit hybrids that produce loose-skinned, tangerine-like fruits. Orlando is an ideal selection for homeowner use. It is cold hardy and produces excellent quality fruits that ripen early (October to December). Dancy, Clementine or some other variety should be planted with Orlando for cross-pollination. Other early-season (October to November) tangerine hybrids that could be grown include Lee, Robinson, Nova, and Page. All of these hybrids require cross-pollination for best fruiting.

'Tango' mandarin was the result of a mutation of the variety 'W. Murcott Afourer', which is a cross between a mandarin and an orange. This attractive variety is seedless, easy to peel, and ripens in early December. The fruit will retain high quality on the tree until March. 'Shiranui' is a high-quality hybrid of a Tangor and Ponkan. It bears large, easy-to-peel fruit that sections easily. Normally, it does not fully ripen until late December, making the fruit more susceptible to freezes.

'Bingo', 'Sugar Belle', and 'Marathon', are three newer varieties released by the University of Florida. 'Bingo' produces small but very sweet, easy-to-peel fruit from mid-October until November. 'Sugar Belle' produces a very attractive, deep-orange fruit that ripens in late December. The flavor is intense, with both a high sugar and acid content. It does not peel or section easily. 'Marathon' ripens beginning in October and can retain quality on the tree until February.

Sweet Oranges

Sweet oranges may be grown along the lower coastal area with a fair degree of success if adequate cold protection is provided each year. 'Hamlin' is suggested if fruits are desired primarily for juice. Its cold-hardiness is equal or superior to other sweet orange varieties; however, hard freezes (20 °F and lower) will severely damage them. Fruits are commercially seedless (six seeds or fewer per fruit) and ripen mid-November to early December. 'Florida EV1' and 'Florida EV2' are two 'Valencia' varieties that mature in January to February which is 8–12 weeks earlier than the standard 'Valencia'.

The navel orange is recommended for growing seedless fruit that will be eaten fresh. Navel oranges often produce light crops and aren't usually as fruitful as sweet orange varieties (non-navel types) such as 'Hamlin'. Suggested varieties include 'Washington', 'Glen', and 'Cara Cara', which is a red navel. All ripen their fruits relatively early (November to December). 'Southern Frost' is a very sweet navel released by the University of Georgia that ripens in late November.

Grapefruit

Because of a lack of outstanding cold hardiness, grapefruit should be grown along the same lower coastal area as sweet oranges. Although numerous selections are available, the 'Marsh' (white seedless) and 'Redblush' or 'Ruby' (red seedless) varieties are the most frequently planted. Both produce excellent quality fruit and have few to no seeds. For those homeowners who prefer exceptionally high fruit quality, the white seedy varieties 'Royal' and 'Triumph' are suggested. 'Marsh' and 'Ruby' fruits may be harvested as early as late September and October, but their quality significantly improves if they remain on trees until November and December. The 'Star Ruby', released by Texas A&M University, is an outstanding red seedless grapefruit. The University of Georgia has released a grapefruit that ripens from late November to March, called 'Pink Frost'. It has a deep pink color and a pink blush on the rind.

Acid Types of Citrus

There are a number of hardy acid-type fruits available for homeowner use. These plants make attractive ornamental specimens and provide delightful fruits. All are self-fruitful and do not require cross-pollination.

Kumquats

Kumquats are the most cold hardy of the commonly grown acid citrus fruits, tolerating temperatures as low as 15 to 17 °F. They possess a delayed resumation of growth in the spring, which helps avoid late freeze damage. The kumquat is one of the most widely used citrus plants around the home and develops into an attractive shrublike tree that bears small orange-like fruit about 1 in. in diameter. Fruits may be eaten fresh, peel and all, or used in making jellies, marmalade, and candies. Many varieties are available, such as 'Nagami', 'Marumi', and 'Meiwa'. 'Nagami' fruit are oblong to pear-shaped and have acid pulp; the others are sweeter and rounder. 'Meiwa', which produces nearly round sweet fruit, has become one of the most popular for home planting.

Calamondins

This small, round fruit looks somewhat like a tangerine and has very acid pulp. It is attractive as an indoor or container plant. Fruits are yellow to orange colored, and are readily used as a substitute for limes and lemons. Calamondins have good cold hardiness (low 20s).

Lemons

Meyer, one of the most cold-hardy lemon selections, is recommended for home planting because it produces good crops of large, practically seedless, juicy lemons. The fruit ripening period usually lasts from November to March. Inherent cold-hardiness approximates that of the sweet orange (mid-20s). The University of Georgia has released a large, cold-hardy lemon called 'Grand Frost', derived from an 'Ichang' lemon.

Lime Hybrids

The 'Lakeland' and 'Eustis' limequats are very cold-hardy lime-kumquat hybrids and make very attractive small trees. Limequats are popular as container plants. Limequats produce fruit resembling the lime in appearance and quality and may serve as an excellent lime substitute. Cold hardiness is about equivalent to the tangerine (low 20s). 'Tavares' is a more upright variety.

For more information on citrus varieties, visit the Givaudan Citrus Variety Collection (citrusvariety.ucr.edu).

Rootstock Selection

Proper rootstock selection is crucial. A grafted tree has the best qualities of a root system that is better able to tolerate diseases, pests, and certain environments. While the scion has the most influence on fruit quality, the rootstock can also influence fruit quality, tree productivity, tree size, and tree cold hardiness.

Trifoliate orange (Poncirus trifoliata) is perhaps the most cold-hardy rootstock. Selections of P. trifoliata are 'Rubidoux', 'Rich 16-6', and 'Flying Dragon'. 'Flying Dragon' is a dwarfing, slow-growing rootstock that produces a smaller tree. Trifoliate orange is an excellent rootstock for satsumas, oranges, kumquats, and tangerines.

Trifoliate hybrids produced by the USDA-ARS also are excellent rootstocks. Examples are 'US-812' and 'US-1516' which show indications of good cold hardiness. 'US-942' is a very productive rootstock. For more information on USDA rootstocks visit Citrus Rootstocks USDA (citrusrootstocks.org) and the University of Florida rootstock selection guide (crec.ifas.ufl.edu/extension/citrus_rootstock/).

Pollination

With the exception of Clementine tangerine and certain tangerine hybrids such as Orlando tangelo, citrus trees are self-fruitful and do not require cross-pollination. Refer to the University of Florida publication HS182, Pollination of Citrus Hybrids (edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/CH082) for pollination requirements. Self-fruitful types of citrus may be grown as single trees.

Establishment and Care of Young Citrus

Site Selection and Spacing

Citrus trees produce fruit best when grown in full sun. Citrus trees planted under live oaks or pines produce only light fruit crops, but often survive freezes since warmer air may be trapped under the sheltering trees.

Avoid planting trees near septic tanks or drain fields. Tree roots may clog the drain, and soaps and cleaning supplies, used in the home may prove toxic to the trees.

Citrus trees do best on well-drained sandy loam soils, but will grow on many soil types if good water drainage is provided. If drainage is problem, plant on wide raised beds. Citrus trees may be planted as close as 8 to 15 ft apart, depending on the rootstock and variety. Small citrus plants such as kumquats may be spaced as close as 6 to 10 ft.

If possible, locate citrus plants in a protected area, such as near a home or some other structure, preferably on a southern- or western-facing slope. Windbreaks on the northern and western sides will help protect trees from advective freezes. This type of location provides maximum protection from severe freezes. Usually the wind associated with South Georgia cold weather comes from the north to northwest.

Purchasing Trees

Citrus trees should only be purchased from a USDA-certified nursery to prevent importing diseases and insects that can kill citrus trees. One such disease is Huanglongbing or HLB. Citrus greening is another name for this bacterial disease that is devastating the citrus industry in Florida, reducing citrus production by over 80% since 2004. This bacterial disease is spread by tiny insects called Asian Citrus Psyllids (ACP). It can also be spread by propagating citrus.

Trees purchased or brought into Georgia from Florida from uncertified nurseries have a good chance of being infected with HLB. Any tree grown or for sale outdoors in Florida or other locations with HLB should not be brought to Georgia. For more information, visit the University of Florida website on citrus greening (crec.ifas.ufl.edu/research/citrus-production/disease-identification/citrus-greening-huanglongbing/).

All trees from USDA-certified nurseries are grown indoors. There are several USDA-certified citrus nurseries in Georgia, Florida, and Texas that will ship certified trees through the mail. There are many other diseases and viruses that infect trees besides HLB. Citrus canker is another serious disease that is very easy to spread to other trees. Citrus canker can damage fruit and defoliate trees. It is spread through wind and rain as well as on clothing, equipment, people, or animals. Before purchasing a citrus tree, make sure the trees are from a USDA-certified nursery or a location without citrus greening.

Tree Selection and Planting Procedures

Most citrus trees for home plantings are purchased in containers, or balled and wrapped in burlap. Caliper is trunk diameter measured 1 in. above bud union; healthy 1-year-old budded trees should be ½- to ¾-in. in caliper and 2-year old trees usually measure ¾- to 1¼-in. in caliper. These trees are the ideal size for home planting. Acid-type fruit plants are usually purchased in smaller sizes. Planting in early spring (after danger of freezing temperatures has passed) is highly recommended and planting in the fall or winter is discouraged. A planting site 4 to 5 ft in diameter should be cleaned of all weeds and grasses and the soil thoroughly spaded.

Dig a hole large enough to accommodate the root ball. Remove the plant from the container and place it in the hole, keeping the top of the root ball level with the soil surface. If the tree is pot-bound, make vertical cuts at several locations around the ball to stimulate new root development. Fill the hole about one-half full with soil, add water, and tamp firmly to settle soil and remove air pockets. Allow the water to settle, finish filling the hole with soil, and apply water again. Pack the soil firmly around the trunk, adding additional soil if needed. Do not apply any fertilizer in the planting hole, as root damage may result. Around the tree, construct a water basin 30 to 36 in. in diameter and 4 in. high. Water twice weekly for the first 2 weeks unless rainfall is adequate. Gradually reduce the number of waterings to once weekly during periods of little or no rainfall.

The first growing season is critical in the life of a citrus plant. Water is essential. Keep an area at least 4 ft in diameter beneath the tree free of weeds and lawn grass to minimize competition for nutrients and water. If dense lawn grass is allowed to reestablish close to the tree trunk, the small tree will grow rather slowly because of intense competition.

At the time of planting, the branches should be cut back to 6- to 12-in. stubs (this pruning is sometimes already completed when plants are purchased). This practice helps balance the top of the tree with the functional root system and stimulates vigorous regrowth. Very little pruning should be required during the first growing season except to remove sprouts that arise below the scaffold limbs (the primary structural branches originating from the tree trunk).

Ideally, scaffold branches should not be allowed to develop lower than 18 to 20 in. from the soil. The natural branching habit of citrus results in structurally sound trees; thus, the type of tree training normally practiced with peaches and apples is unnecessary.

Fertilization

Newly planted trees should not be fertilized until growth begins in the spring. If possible, use a complete fertilizer such as an 8-8-8 or 10-10-10 that contains micronutrients. A suggested fertilizer schedule for the first 3 years is given in Table 1. Fertilizer applications should not be made between August 1 and February 15 to avoid inducing untimely growth flushes during the winter.

During the first year, spread fertilizer in a 30-in. circle, and avoid placing any against the trunk. In subsequent years the fertilized area should be gradually increased. A good rule of thumb is to fertilize an area twice the diameter of the tree canopy.

Ordinary lawn and shrub fertilizer may be used for citrus trees; however, it may only contain the primary plant food elements of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. For the best performance, apply a fertilizer containing secondary and micronutrients. Micronutrients can also be supplied through nutritional sprays. Some garden centers and nurseries sell special citrus fertilizers that incorporate micronutrients. Tissue analysis can be done in early August to determine if the tree is deficient or has an excess of any nutrients.

Cold Protection

Even the most cold-hardy young citrus trees cannot withstand freezing temperatures as well as more mature, bearing trees. Before the first freeze, trees up to 4 years of age should be banked with clean soil to a height of about 15 in. Soil banks should be removed after the last chance of freeze in the early spring. Wrapping material with good insulating properties such as fiberglass or foam rubber also make effective protectors and may be used in lieu of soil banks. These materials should be a minimum of 6 in. thick and must make good contact with the soil. Special microsprinklers placed up against the trunk can also be used to protect the trunks during freezes, but they have to run continuously until the temperature is above freezing and at least 8 gallons per hour are needed. If water is applied over the top, the ice load will break the limbs. When the trees grow larger, the microsprinkler is placed in the lower part of the tree to protect the trunk and lower scaffold limbs.

When only a few plants are involved, protective covers such as blankets or frost cloth may be used when severe freezes occur. If possible, the cover should be large enough to cover the tree and extend to the ground where the cover can be held down with bricks or something to keep the wind from blowing it away. On extremely cold nights, placing one or two electric light bulbs beneath the cover provides good protection.

Cold Hardiness and Factors Affecting Freeze Damage

Citrons, lemons, and limes are most easily killed by freezing temperatures. Temperatures from the mid- to high-20s will readily kill or severely damage these plants. Sweet oranges and grapefruit are somewhat more cold hardy and usually require temperatures in the low- to mid-20s before incurring major damage to large branches. Tangerines and mandarins are quite cold hardy, usually withstanding temperatures in the low 20s before significant wood damage occurs. Among the edible types of sweet citrus, the satsuma and changsha have the greatest degree of cold hardiness. Properly hardened bearing trees will withstand temperatures as low as 15 °F without appreciable wood damage.

Citrus fruits on the other hand easily freeze at 26 to 28 °F, especially when these temperatures last for several hours. A longer duration of freezing temperatures is required to freeze grapefruit (because they have a thicker peel) than sweet oranges and tangerines.

In addition to the citrus variety, the particular temperature at which tissue of a given plant will freeze and the degree of the damage sustained are functions of a number of factors:

- the freezing temperature reached;

- the duration of the minimal temperature;

- how well the plant became hardened or conditioned before freezing temperatures occurred (the tissue freezing point of a hardened citrus plant may be 5 to 6 degrees lower than an unhardened plant);

- whether the plant is wet or dry (the killing temperature is 2 to 4 degrees lower for a dry citrus plant);

- the age of the plant (a young plant cannot withstand as much cold as a more mature tree);

- the rootstock onto which the scion is grafted, as some rootstocks induce dormancy better than others;

- tree health (healthy trees are more likely to survive freezes); and

- the fruit load on the tree (unharvested trees or trees with a fall crop are more likely to be damaged, so harvest as soon as possible before a freeze event).

Some years, citrus plants seem to freeze at higher temperatures. The contributing factor seems to be the difference between air (ambient) temperature and leaf (tissue) temperature. On a windy night with clear or cloudy skies, leaf temperature will be approximately the same as air temperature. On a cold, clear night with little or no wind movement, leaf temperature may easily drop 3 to 4 °F below air temperature because of radiation heat loss. For example, while the minimum air temperature on a given night may have been 25 °F, actual leaf temperature may have reached 21 to 22 °F. The critical temperature is that of the leaf or fruit, not the air.

Care of the Bearing Tree

The first 3 years should be devoted to developing a vigorous tree with strong scaffolds. Some fruit may be borne the second and third growing seasons, although the quality may not be too good. Trees should begin fruiting significant crops in the fourth growing season. Before you allow a tree to bear fruit, make sure the tree is strong enough to support the load.

Continue using the same 8-8-8 fertilizer (or equivalent) with micronutrients for bearing trees. Apply fertilizer from near the trunk to well beyond the leaf drip of the tree (on large trees this usually involves fertilizing about 4 to 6 ft beyond the leaf drip). A reasonable rate of application to maintain healthy foliage and good fruiting is about ½ lb of 8-8-8 fertilizer per year of tree age (rates are for sandy soils; clay and other soils with greater inherent fertility require less fertilizer). After a number of years, a fertilizer containing nitrogen and potassium or just nitrogen alone may prove adequate.

As trees age, problems may be encountered with micronutrient deficiencies. An annual nutritional spray applied in the spring usually corrects the deficiencies. Prepackaged nutritional spray mixes may be purchased from garden supply dealers. These mixes should contain manganese, zinc and copper. Boron deficiencies may be corrected with foliar sprays or soil applications. When iron deficiency symptoms develop, chelated forms should be applied to the soil.

The pH (acidity or alkalinity) of the soil in which trees are growing should be maintained between 6.0 and 7.0. Apply dolomite, agricultural limestone, or basic stag as needed to prevent the pH from dropping below 6.0. Your local county Extension agent or garden supply dealer can assist in determining if a pH adjustment is needed.

Weed control around large bearing trees becomes somewhat less essential. However, it is generally beneficial to remove all weeds and lawn grass from beneath the canopy of the tree. This approach also provides a more attractive landscape design. Do remove weeds and grass from the area immediately around the tree trunk as this growth tends to create ideal conditions for fungal organisms, such as those causing foot rot at the base of the tree. Mulches are not necessary for best tree performance, but may be used on well-drained sites. Mulching material should not be placed within 12 in. of the trunk.

Watering bearing citrus plants will not be necessary in some years. However, adequate water should be provided as needed, particularly during flowering and fruit setting in early spring and the dry periods of mid- to late summer. A slow application of water over a period of several hours is preferable to a rapid lawn-type irrigation.

Pruning citrus trees on an annual basis is unnecessary. Only remove water sprouts (suckers) and dead, damaged, or diseased limbs. Make all cuts flush with the trunk or the next-largest branch (don't leave stubs). Seal all cuts in excess of ½ in. in diameter with a safe pruning paint—those with an asphalt base are recommended. The summer is usually an ideal time for pruning.

Citrus plants in Georgia are always subject to injury from cold weather. If trees are only slightly damaged, pruning may be done as soon as new growth indicates the extent of injury. However, regardless of the amount of injury sustained, no pruning should be done until after danger of further freezes has passed. If trees incur major freeze damage, allow the first flush of growth to mature before pruning.

Other Cultural Problems

Fruit Shedding

Homeowners frequently become concerned about the excessive shed of young blossoms and fruits in early spring. This is a natural shedding of blossoms and fruits that is characteristic of all citrus. Another natural fruit shedding occurs in May and June when fruits are marble-size. Keep in mind that only 1% or 2% (sometimes less than 1%) of the blossoms are needed for good crops. Natural shedding of flowers and fruits prevents citrus from overproducing.

Leaf Drop

Occasionally homeowners become alarmed when healthy trees lose large numbers of their leaves. In many cases this is a natural drop; and may be most noticeable in early spring. Citrus leaves live for 18 to 24 months and then begin shedding, with some leaf dropping occurring throughout the year. Always be alert to other possible causes of leaf shedding, including mite damage, excessive or insufficient soil moisture, cold damage, or root diseases.

Fruit Splitting

In late summer (August to September), fruit splitting may be a problem with certain oranges and tangerines. This is a physiological problem that usually occurs when a period of fruit growth cessation (associated with moisture stress) is followed by a rapid increase in size as the result of a heavy rain. Other than alleviating moisture stress, little can be done about this problem.

Insect and Disease Control

Citrus fruits may be grown successfully in the home or backyard orchards with limited control of insects and diseases. Fruits produced without pesticide sprays may have very poor external quality as a result of mite, insect, and fungus disease damage. The tree appearance may suffer, but they are seldom critically damaged by most citrus pests. Natural biological control will assist in maintaining pests at low population levels.

For those who prefer to spray, three cover sprays during each season are helpful. A postbloom spray for scales, mites, and fungal diseases; a summer oil for scales and mites; and a fall mite spray are usually satisfactory.

Formulating a spray program can be somewhat difficult because of the many factors involved, including constantly changing government regulations regarding the use of agricultural chemicals. Consult your local county Extension agent for information on developing a spray program for home citrus trees.

Status and Revision History

Published on Jan 08, 2009

Published with Full Review on Feb 14, 2012

Published with Full Review on Feb 22, 2015

Published with Full Review on Feb 01, 2020

Published with Minor Revisions on Oct 24, 2024