Clean Labeling and the “Real Food” Movement

“Clean labeling” is a consumer-driven initiative that encourages food developers to create products with easy- to-understand labels, listing natural ingredients and minimal artificial additives. Many major food companies (like Campbell Soup Company, Nestlé, and Mars) have committed to removing artificial food additives, and clean labeling is driving innovations in food product development. To stay competitive, the practice of creating clean labels is becoming more of a necessity than a trend in the U.S. and across the world.11 A successful clean- label revolution requires food producers to deeply understand consumer viewpoints, but many consumers do not know or agree upon what a clean label is.3,10 Moreover, it is not easy process for food companies to switch from artificial to natural ingredients overnight. This publication will discuss a clean labeling in detail from both consumer and industry points of view.

Defining a “clean label”

A food label requires five components:

- A statement of identity;

- the net weight of the product;

- the manufacturer’s address;

- the nutrition facts; and

- the ingredient list with allergen and health claims.

Currently, there is no regulatory or legal definition for “clean label.” The term is characterized both from the consumer’s perception of what “natural” suggests and by the ways food manufacturers market their products. The meaning of “clean label” may be different to different people, but it tends to involve the following concepts:2,10

- Natural ingredients: no artificial flavors, artificial colors, artificial preservatives, or synthetic additives.

- Simplicity: less chemicals and recognizable ingredients that do not sound chemical or artificial.

- Transparency: information on how ingredients are sourced and how products are manufactured.

- Minimal processing: processing using techniques that consumers don’t understand to be artificial.

Consumers may identify a clean-labeled product by a shorter ingredient list or terms like “natural,” “simple,” “no artificial,” and “no preservatives” on the food label.

Consumer insights

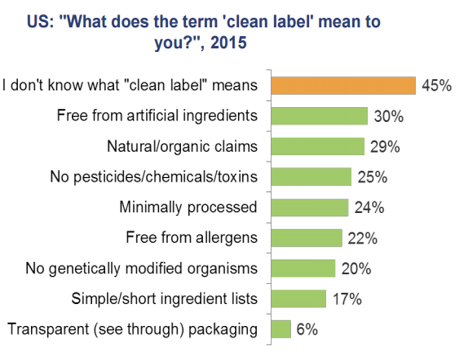

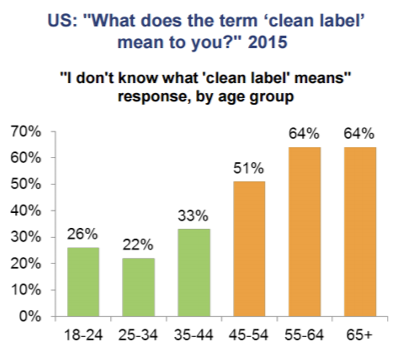

The clean-label phenomenon emerges from a series of food incidents that occurred around the world, according to Ewa Hudson, the global head of health and wellness, nutrition, and ethical labels research for Euromonitor. Worldwide food scandals and negative research results about artificial ingredients increased consumers’ concerns about food quality and raised their desire for natural food products.5 Although clean labeling was catalyzed by consumer demand, its meaning is unclear to many consumers. A 2015 U.S.-based survey indicates that 45 percent of U.S. consumers do not know what “clean label” means and there is a generation gap (age 18 to 44 years vs. 45 years and above) in the understanding of this term (Figure 1).10

Moreover, the perceptions of clean labeling vary by age. Respondents aged 18 to 34 correlate “clean label” with “natural” or “organic” claims, which aligns with the segment aged 35 to 44, a population that also takes “minimally processed” into consideration. Consumers over 44 equate the term “clean label” with “free from bad ingredients.”10

The differences between “natural” and “organic” labeling

From a consumer perspective, a clean label may be associated with claims that a product is “natural” or “organic,” but there are differences between the two.

The “Natural” claim

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has no regulatory definition for “natural”-related labeling, but it clearly states that “The agency has not objected to the use of the term if the food does not contain added color, artificial flavors, or synthetic substances.”9 In 2016, the FDA requested information and public comments on the use of the term “natural” and may describe the tenets this claim more precisely in the near future.8 The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) considers “natural” to be a “product containing no artificial ingredient or added color and is only minimally processed.” Minimal processing means that the product was processed in a manner that does not fundamentally alter the product. The label must include a statement explaining the meaning of the term “natural,” such as “no artificial ingredients; minimally processed.”6 USDA has also developed a decision tree to classify synthetic and non-synthetic (natural) materials.7

According to FDA and USDA, the major difference between “natural” and “clean label” claims relies mainly on food colorings. Natural colorants (like carotenoids and anthocyanins) are not allowed in natural labeling, but are acceptable in clean labeling.

The “Organic” claim

“Organic” refers to more than the food product itself. Its way of production must meet strict standards of National Organic Program (NOP) administered by USDA Agricultural Marketing Service. There are four categories of “organic” labeling based on product composition, and the specifications are available on the Organic Labeling Standards website.

Some compounds permitted by NOP in organic food products are unacceptable in clean-label products, such as potassium bicarbonate, ammonium bicarbonate, and calcium hydroxide.2

Industry activities

Without the ability to formally define a “clean label,” food companies, restaurants, and retail stores take their own actions to respond to consumer demand for clean-label products. Many major manufacturers have committed to narrow down their ingredient list (Table 1), and some of them also put explanations about controversial ingredients on the label to make them sound “clean” or “natural” to consumers.2 Some food companies adopt other strategies like ingredient counts to communicate the clean-label concept.10

Challenges to the progress of clean labeling

The clean-label movement is complicated and full of challenges. The first consideration is the functionality of natural ingredients. Many chemicals or additives are used to ensure the safety of food or to maintain shelf life. For example, essential oils from herbs and spices have been proven to have antimicrobial properties, which make them promising substitutes for preservatives. However, their efficacy must be fully investigated before replacing current preservatives.1 The second consideration is the effect of such a change on sensory attributes. Using spices as preservatives may introduce their unique flavors, which could be either pleasant or detrimental depending on individual food products. It should also be noted that clean labeling involves more than removing ingredients, because these ingredients may not work alone in food products. Take flavored beverages as an example: the oil-based flavor agent needs the help of an emulsifier to disperse it throughout the water-based drink. Simply eliminating the emulsifier will lead to a huge change in the sensory characteristics, including appearance and flavor.4 In addition, costs and regulations (like labeling, usage limit, and GRAS, Generally Recognized as Safe, regulations) must be addressed by manufacturers.1

Table 1. Clean-label statements from selected food manufacturers.

|

Food Manufacturer |

Statement on Ingredients |

|---|---|

|

Kraft removed artificial preservatives, flavors, and dyes from Kraft Macaroni & Cheese. |

|

Nestlé USA removed all artificial colors from chocolate candy products, and removed artificial flavors from entire line of frozen pizza and snacks |

|

Panera Bread has a “no-no” list that contains artificial preservatives, sweeteners, and flavors, as well as colors from artificial sources. |

|

Papa John’s Pizza removed 14 artificial ingredients. |

|

Simple Truth’s “Free From 101” removed 101 artificial preservatives and ingredients. |

|

Whole Foods Market banned many artificial colors, flavors, preservatives, and sweeteners. |

|

Campbell’s Soup Company pledged to remove artificial colors and flavors from its North American products by 2018 and launched Well Yes! soups, which have no artificial colors, flavors, ingredients, or modified starches. |

|

Dannon pledged to use more natural ingredients in Dannon®, Oikos®, and Danimals® branded products. |

|

General Mills pledged to remove artificial ingredients from all of its cereal products by the end of 2017. |

|

Kellogg’s pledged to remove artificial colors and flavors from its products by the end of 2018. |

|

Mars pledged to remove artificial colors from its human food products over five years in a February 2016 announcement. |

|

Subway pledged to remove artificial flavors, colors, and preservatives from its North American food products by 2017. |

|

Unilever removed artificial colors and flavors from many products. |

The future of clean labeling

“Food Business News” reported an estimated $165 billion in global sales of clean-label foods and beverages in 2015, with $62 billion from North America. Global sales may reach $180 billion by 2020.5 This suggests that despite the time and rigorous testing required to ensure the safety and quality of alternative ingredients, an increasing number of food manufacturers will follow the clean labeling movement.

References

1Chen, W., & Hart, H. (2016, October 11). Consumers turn an eye to clean labels. Food Safety Magazine. http://www.foodsafetymagazine.com/magazine-archive1/octobernovember-2016/consumers-turn-an-eye-to-clean-labels/

2Hutt, C. A., & Sloan, A. E. (2015, March 31). Coming clean: What clean label means for consumers and industry [Conference presentation]. Global Food Forum Clean Label Conference. https://cleanlabel.globalfoodforums.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2020/08/Natural-to-Non-GMO-Info-for-Regulators-Consumers-C-A-Hutt-RdR-Solutions-Consulting-2015.pdf

3Gelski, J. (2016, February 19). Consumers not clear on clean label definition. Food Business News. https://www.foodbusinessnews.net/articles/7407-consumers-not-clear-on-clean-label-definition

4Marrapodi, A. (2015, March 17). New drinking culture: Getting your beverage clean label ready. Natural Product Insider: The Clean-Label Beverage Issue. https://www.naturalproductsinsider.com/ingredients/clean-label-beverage-issue

5Nunes, K. (2016, October 6). Clean label — A $180 billion global opportunity. Food Business News. https://www.foodbusinessnews.net/articles/6980-clean-label-a-180-billion-global-opportunity

6U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2015). Meat and poultry labeling terms. https://www.fsis.usda.gov/food-safety/safe-food-handling-and-preparation/food-safety-basics/meat-and-poultry-labeling-terms

7U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2016). Decision tree for classification of materials as synthetic or nonsynthetic (Publication No. NOP 5033-1). https://www.ams.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media/NOP-Synthetic-NonSynthetic-DecisionTree.pdf

8U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2018). Use of the term natural on food labeling. https://www.fda.gov/food/food-labeling-nutrition/use-term-natural-food-labeling

9U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2017). What is the meaning of ‘natural’ on the label of food? Retrieved May 1, 2017, from http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/Transparency/Basics/ucm214868.htm

10Vierhile, T. (2016, March 29). Clean label focus: What are consumers saying and what is the industry doing? [Conference presentation]. 2016 Clean Label Conference. https://cleanlabel.globalfoodforums.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2020/08/Clean-Label-Focus-Consumers-vs-Industry-Response-Tom-Vierhile-Innovation-Insights-2016.pdf

11Watrous, M. (2015). Trend of the year: Clean label. Food Business News. Retrieved May 1, 2017, from https://features.foodbusinessnews.net/corporateprofiles/2015/trend-index.html

Status and Revision History

Published on May 22, 2017

Published with Full Review on May 10, 2023