- Introduction

- Importance of Body Condition Scoring

- How to Body Condition Score

- When to Evaluate Body Condition

- Body Condition Score and Calving Season

- Increasing Body Condition Score from Calving to Breeding

- Supplementing Feeding Based on Body Condition Score

- Extended Breeding Season

- Salvaging the Breeding Season

- Management Factors Affecting Body Condition Score

- Summary

- References

Introduction

Reproduction is the most important factor in determining profitability in a cow calf enterprise. To maintain a calving interval of 365 days, a cow must re-breed in 80 to 85 days after calving. Many cows in Georgia need a higher level of condition at calving and breeding to improve reproductive performance. Poor reproductive performance is directly linked to the percentage of body fat in beef cows. Body condition scoring (BCS) is an easy and economical way to evaluate the body fat percentage of a cow. Cows can then be sorted and fed according to nutritional needs. Body condition scoring can be an effective tool for cattle producers who cannot weigh cattle, and it may be an even better measurement of cow condition and reproductive performance than weight. Most studies show that body condition decreases at a faster rate than weight loss. Therefore, body condition scoring can estimate the probability of re-breeding.

Beef cattle have nutrient requirements in priority order for body maintenance, fetal development, lactation, growth and breeding. The nutrient intake is distributed in the body of the cow to fill these nutrient requirements. As each requirement is filled, the available nutrient is shifted to the next lower priority. The reverse shift is also obvious in beef cows. As nutrient requirements exceed intake, nutrients are shifted from the lower priority requirements to be sure that higher priority requirements are filled. Beef cattle store excess nutrients as body fat. The fat stores are mobilized when the nutrient demands exceed the available intake. In times of severe nutrient restriction, muscle tissue is mobilized once fat and other nutrient stores have been depleted. Researchers have determined that a certain amount of body fat is required for the reproductive system to function. Inadequate nutrition is most often the cause of poor reproductive performance. Developing a nutrition program is easier and more cost effective when all cows on the farm can be managed in a similar manner. This is especially true when all cows on a farm are managed in a single herd, which is often the case with small production units. Calving year-round will make it very difficult to maintain adequate body condition on all cows at the critical times.

Importance of Body Condition Scoring

Body condition affects both cow and calf performance. Poor body condition is associated with reduced income per cow, increased postpartum interval, weak calves at birth, low quality and quantity of colostrum, reduced milk production, increased dystocia, and lower weaning weights. Increasing postpartum interval will result in a younger, smaller calf at weaning the next year and will result in lower incomes if sold at weaning. Weak calves at birth may not get adequate colostrum and are more susceptible to disease, reduced weaning weights, reduced feedlot performance, and less desirable carcass traits. Research clearly shows that cows in moderate body condition will have a shorter interval from calving to first estrus than cows in thin condition. This supports the conclusion that BCS is one of the most important factors in determining subsequent reproductive performance.

Table 1. Description of body condition scores (BCS).

| BCS | % Body Fata |

Detailed Descriptionb |

|---|---|---|

| Thin | ||

| 1 | 3.77 | Clearly defined bone structure of shoulder, ribs, back, hooks and pins easily visible. Little muscle tissue or fat present. |

| 2 | 7.54 | Small amount of muscling in the hindquarters. Fat is present, but not abundant. Space between spinous process is easily seen. |

| 3 | 11.30 | Fat begins to cover loin, back and foreribs. Upper skeletal structures visible. Spinous process is easily identified. |

| Borderline | ||

| 4 | 15.07 | Foreribs becoming less noticeable. The transverse spinous process can be identified by palpation. Fat and muscle tissue not abundant, but increasing in fullness. |

| Optimum | ||

| 5 | 18.89 | Ribs are visible only when the animal has been shrunk. Processes not visible. Each side of the tail head is filled, but not mounded. |

| 6 | 22.61 | Ribs not noticeable to the eye. Muscling in hindquarters plump and full. Fat around tail head and covering the foreribs. |

| 7 | 26.38 | Spinous process can only be felt with firm pressure. Fat cover in abundance on either side of tail head. |

| Fat | ||

| 8 | 30.15 | Animal smooth and blocky appearance; bone structure difficult to identify. Fat cover is abundant. |

| 9 | 33.91 | Structures difficult to identify. Fat cover is excessive and mobility may be impaired. |

| 1 [thin] to 9 [obese]a aSource: National Research Council, 2000. bAdapted from: Herd and Sprott, 1986. |

||

How to Body Condition Score

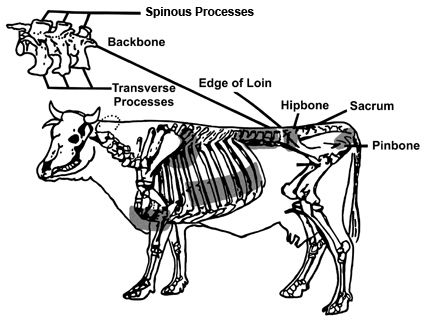

To properly evaluate body condition for cattle, an observer must be familiar with skeletal structures and with muscle and fat positioning. Although there are several methods available to determine body composition, many cattle producers use a scoring system that involves ranking cattle on a scale. This manuscript will focus on the commonly used scale of 1 to 9, with 1 being emaciated and 9 being obese (Whitman, 1975).

Cattlemen can easily observe cattle under pasture conditions to obtain body condition scores. Familiarity with key skeletal structures listed in Figure 1 is required to apply an accurate body condition score. A description of each condition score is listed in Table 1.

Figure 1. Skeletal structures of a cow used to evaluate body condition score.

BCS 2

BCS 2 BCS 3

BCS 3

BCS 4

BCS 4 BCS 5

BCS 5

BCS 6

BCS 6 BCS 7

BCS 7

Body condition scoring is a subjective measurement, meaning that one producer may score slightly different than another. The producer can gain experience using body condition scores by identifying cattle into one of three categories: thin (1 to 3), borderline (4), optimum (5 to 7) or too fat (8 and 9). Over time, as the producer becomes familiar with details of each specific body condition score, these categories can be further broken into actual condition scores. Research reported by the University of Florida (Table 2) demonstrates that as cattle decrease from a body condition score of 5 to 4, they may have reduced pregnancy rates by as much as 30%. An additional 30% of pregnancies can be lost when cattle drop from a 4 to a 3. Cattle that receive a BCS of 5 or below may have reduced pregnancy rates. Although most cattlemen tend to keep cows on the thin side, cattle that are obese (BCS of 8 to 9) may also have reduced pregnancy rates.

Table 2. Relationship of parity and body condition score to pregnancy rate (%).a

| Body Condition Scoreb at Calving | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parity | < 3 | 4 | > 5 | All |

| 1 | 20 | 53 | 90 | 84 |

| 2 | 28 | 50 | 84 | 71 |

| 3 | 23 | 60 | 90 | 85 |

| 4-7 | 48 | 72 | 92 | 87 |

| > 8 | 37 | 67 | 89 | 74 |

| All | 31 | 60 | 89 | 82 |

| aRae et al., 1993. bScale of 1 [thin] to 9 [obese] |

||||

Table 3 shows the impact of BCS on pregnancy percentage, calving interval, calf performance, calf price and income. Cows in a borderline body condition (BCS of 4) have greatly reduced pregnancy rates, increased calving intervals, lower calf daily gain and greatly reduced yearly income. For example, a cow calving in a BCS of 4 will return an income of approximately $100 less than a cow calving in a BCS of 5. If BCS is taken 90 days prior to calving, the cows in borderline condition can be properly supplemented to achieve a BCS of at least 5 at calving. In most cases supplemental feed costs will be approximately $25 to $35 for feed that costs $100 to $150 per ton. This is far less money spent on feed than would be lost if cows were allowed to stay in a BCS of 4. The impacts are even greater for a BCS of 3 and is a condition that should never happen with any of the cows in the herd.

Table 3. Relationship of body condition score to beef cow performance and incomea.

| BCSb | Preg. Rate (%) |

Calving Interval (days) |

Calf WA (days)c |

Calf DG (lb)d |

Calf WW (lb)e |

Calf Price $/100f |

Income ($/Calf) |

Yearly Income $/Cowg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 43 | 414 | 190 | 1.60 | 374 | 96 | 359 | 142 |

| 4 | 61 | 381 | 223 | 1.75 | 460 | 86 | 396 | 222 |

| 5 | 86 | 364 | 240 | 1.85 | 514 | 81 | 416 | 329 |

| 6 | 93 | 364 | 240 | 1.85 | 514 | 81 | 416 | 356 |

| aAdapted from Kunkle et al., 1994. bBody condition score; scale of 1 [thin] to 9 [obese]. cWeaning age; 240 days for cows in BCS 5 and 6 and decreasing as calving interval increases. dDaily gain. eWeaning weight; calculated as calf age multiplied by calf gain plus birth weight [70 lbs]. fAverage price for similar weight calves during 1991 and 1992. gCalculated as income/calf times pregnancy rate times 0.92 [% calves raised of those pregnant]. |

||||||||

When to Evaluate Body Condition

Many beef producers are involved in diversified farming operations. These operations may combine cattle with row crops, poultry houses, timber and many other time consuming production practices. Regardless of the combination, additional obligations may limit the amount of time producers can spend evaluating body condition. However, neglecting to properly observe and record body condition can have a substantial impact on overall productivity and profits.

To properly identify cattle that have increased nutritional needs, producers should evaluate body condition as often as possible, but a minimum of three times (weaning, 90 days pre-calving and breeding) per year is preferred. Cattle that are calving should have enough body condition to allow for a reduction in body mass due to weight being lost during the parturition process and fluids being displaced. Body condition score at calving time provides the best prediction of re-breeding performance. Evaluating BCS approximately 90 days prior to calving allows sufficient time to adjust the feed ration to ensure cows are in adequate body condition at calving.

Weaning

Evaluating body condition at weaning can be useful to determine which cows or heifers need the most gain prior to calving. Since calves will no longer suckle, lactating cows will be able to dry off and add needed weight before calving. The time period from weaning to calving has proven to be the easiest and most economical time to add condition to cattle. Producers who fail to evaluate body condition and adjust the nutritional needs of the cow herd after weaning may have difficulty adding condition later in the production cycle.

90 days Prior to Calving

Assessing body condition 90 days prior to the beginning of the calving season may be useful in preventing extended periods of anestrus. This score may be taken at weaning in herds that delay weaning until calves are 8 to10 months of age. However, weaning calves at least 90 days prior to the start of the calving season is recommended. Cow nutritional requirements are greatly lowered when non-lactating and should allow the cow to achieve adequate body condition at calving with minimal supplemental feeding. Nutrition can then be adjusted for cattle that receive body condition scores of less than 5 after this assessment. Although changes in weight can be achieved, take care to prevent excessive weight gain immediately prior to calving. Cows should be fed to calve in a BCS of 5 to 6 and heifers a BCS of 6.

Breeding

After undergoing the stress of parturition, cattle will lose body condition. The time period from calving to breeding is the most difficult in which to improve body condition. This is why it is very important to body condition score cows 90 days prior to calving and make ration changes to achieve optimum BCS prior to calving. Approximately 90% of cattle in optimum body condition will resume estrus cyclic activity 60 days postpartum. Assessing body condition at breeding may offer useful information that may help explain reduced pregnancy rates.

Body Condition Score and Calving Season

The calving season in Georgia varies widely among cattle operations, but most calves are born from September through March. Calving season has a large impact on phase of the cow’s yearly production cycle in which body condition score is most likely to be deficient.

In the southeast, cows calving in the fall months are likely to have adequate body condition score, so the winter feeding period usually begins shortly after the calving season begins. Therefore, cows are lactating throughout the winter feeding period. Increased demands of lactation and declining feed quality during the fall months often causes inadequate body condition by the start of the breeding season, which begins in early- to mid-winter. The majority of producers feed hay as the base diet during this period. Hay will likely require supplementation and the hay feeding period may last throughout the breeding period for cows calving during the fall. In contrast, cows calving in late winter will be in late gestation and early lactation during the winter feeding period. Body condition score at calving will have to be monitored more closely than fall calving cows as the cows will be fed hay through most of the last trimester. Cows will likely be fed a hay based diet that requires supplementation during the early lactation period. However, supplementation can cease when hay feeding stops and grazing becomes available. Cows should be able to increase body condition score when grazing lush spring growth of fescue, ryegrass, or small grain pasture.

Increasing Body Condition Score from Calving to Breeding

The easiest and most economical time to improve body condition score is from weaning to calving. In situations where cows calve in a less than adequate body condition, weight gain must be increased rapidly following calving to achieve acceptable pregnancy rates at the end of the breeding season. The most difficult period to maintain body condition is from calving to breeding. Body condition score and re-breeding rates can be improved in cows calving in less than a 5 condition score if fed to increase condition prior to the beginning of the breeding season. Mature cows, however, will respond to supplementation much better than first calf heifers. Table 4 illustrates the effects of body condition score at calving and subsequent body weight gain on pregnancy rates of first calf heifers. Heifers that calved in a body condition score of 5 or above had greater than 90% pregnancy rates when either gaining weight or maintaining weight. In heifers calving in a BCS of less than 5, pregnancy rate was increased from 36% to 67% by increasing daily gain from 0.7 to 1.8 lb per day. Even though increasing daily gains improved pregnancy rates, the 67% pregnancy rate is not acceptable and was far below both groups calving in a condition score of 5 or greater. This study shows that, for first calf heifers, body condition score at calving is the key component to high re-breeding rates.

Table 4. Effects of calving BCS and subsequent weight gain on reproductive performance of first calf heifers. a

| Calving BCS | Weight gain, lb/db |

Pregnancy % |

|---|---|---|

| < 5 | 1.8 | 67 |

| < 5 | 0.7 | 36 |

| > 5 | 1.0 | 94 |

| > 5 | 0.1 | 91 |

| aAdapted from Bell, et al. 1990. bWeight gain = daily weight gains from calving to the start of the breeding season. |

||

Body condition score at calving is less critical for mature cows. Certainly, it is ideal to have cows in a body condition score of 5 at calving through breeding. Acceptable re-breeding rates, however, can be achieved in mature cows that calve in borderline (BCS of 4) condition if cows are fed to increase body condition score to a 5 at the start of the breeding season.

A study evaluated the effects of nutrient intake from the second trimester through the start of the breeding season. The first group was fed to maintain a body condition score of 5 from the second trimester to the start of the breeding season. The second group was fed to be a BCS of 4 during the second trimester, and then regain condition during the third trimester to a BCS of 5 at calving. The third group was fed to be in a BCS of 4 from the second trimester through 28 days post-calving, and then gain weight to be in a BCS of 5 at the start of the breeding season. Table 5 shows the body condition scores and Table 6 shows the post-calving weight gains and pregnancy rates. All groups were in a BCS of 5 just prior to the start of the breeding season as planned. Acceptable pregnancy rates occurred in all groups. Cows that calved in a BCS of 5 to 6 lost weight from calving to the start of the breeding season; cows that calved in a BCS of 4.8 had to be fed to gain 3.43 lbs per day to increase body condition to maintain an acceptable re-breeding rate. Such rapid weight gain would require a grain-based or corn silage based diet. Cows in a BCS of less than 5 at calving should be separated from the rest of the herd and a feeding program designed to increase BCS should begin immediately. The cows that calved in a BCS of 4.8 were only slightly below the desired BCS of 5 and cows calving in a BCS of less than 4 may not have acceptable pregnancy rates.

Table 5. Effect of restricted feeding on body condition score of mature cows.a

| Feeding Levelb | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Days from Calving | High-High-High | Low-High-High | Low-Low-High |

| -95 | 6.0 | 5.3 | 5.4 |

| 0 | 5.6 | 5.5 | 4.8 |

| +58 | 5.2 | 5.1 | 5.2 |

| aAdapted from Freetly et al., 2000. bHigh-High-High = maintain BCS of 5.5 from weaning to breeding. Low-High-High = decline in BCS in second trimester and regain BCS to a five during third trimester. Low-Low-High = decline in BCS during second trimester through 28 days postcalving, then regain BCS to a five at breeding. |

|||

Table 6. Effect of restricted feeding on postpartum weight gain and pregnancy rates of mature cows.a

| Feeding Levelb | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Item | High-High-High | Low-High-High | Low-Low-High |

| Weight gain, lb/d | -0.46 | -0.64 | 3.43 |

| Pregnancy rate, % | 93 | 92 | 88 |

| aAdapted from Freetly et al., 2000. bHigh-High-High = maintain BCS of 5.5 from weaning to breeding. Low-High-High = decline in BCS in second trimester and regain BCS to a five during third trimester. Low-Low-High = decline in BCS during second trimester through 28 days post-calving, then regain BCS to a 5 at breeding. |

|||

Supplemental Feeding Based on Body Condition Score

Grouping by Body Condition Score

A body condition scoring system is much more effective when cows can be sorted and supplemented relative to target body condition score. The amount of sorting will depend on the availability of pastures and labor. Ideally, mature cows should be separated into an adequate (≥ 5 condition score) and inadequate BCS group (< 5 condition score). In addition, first-calf heifers and developing heifers should remain in separate groups. Condition scores of heifers do not vary as greatly as those of mature cows, and heifers can usually be fed together.

Another option is to sort your cow herd into mature cows in condition score of 5 and greater in one group and heifers plus cows in condition score of less than 5 in another group. The primary benefit of grouping by body condition is to reduce supplemental feeding costs and implement a more specialized management system for thin cows.

Determining Needed Level of Supplementation

Body condition scores of cows must be determined prior to the beginning of a supplemental feeding program. Body condition score has a significant impact on the requirement for energy but only a small effect on the protein requirement. Many supplementation programs focus only on supplemental protein and fall short of providing enough energy to maintain an adequate BCS. Energy rather than protein is often the most limiting nutrient in Georgia forages.

To increase body condition, the first step is to determine how many pounds a cow needs to gain to reach the desired BCS. To increase one condition score, a cow needs to gain about 75 lb. A dry pregnant cow would need approximately 375 lb and a lactating cow 575 lb of total digestible nutrients (TDN) above maintenance to increase one body condition score in a 75-day period. This would equate to approximately 6.5 lb of corn per day for a dry pregnant cow and 10 lb of corn per day for a lactating cow.

Tables 7 and 8 list the requirements for TDN and crude protein for cows and heifers in different body condition scores. For example, a cow that is in body condition score of 4 at 60 days prior to calving needs to gain about 1.25 lb per day to reach a condition score of 5 at calving.

The next step is to determine if the feedstuffs available on the farm will support this gain. For example, a nutrient analyses indicated that the hay was 10% crude protein and 50% TDN. Assume that a dry cow will consume about 2.0% of body weight per day and a lactating cow will consume about 2.25% of her body weight per day in dry feed. Therefore, the dry cow in a body condition of 4 will consume about 24 lb of hay per day. The 24 lb of hay at 50% of TDN will yield 12 lb of TDN. From the information in Table 7, the cow needs 16 lb of TDN. Therefore, the cow must be supplemented with 4 lb of TDN per day. There are many grains, by-product feeds and supplements that will work. The primary factor in determining which supplement to use is price. The crude protein supplied by the 24 lb of hay is about 2.4 lb per day, and the cow requires 2.1 lb per day. Therefore, the supplemental feed does not have to be high in crude protein, and high energy, low crude protein feeds such as corn can be used. In most cases, hay will not supply sufficient nutrients to increase body condition score. Computer ration balancing programs are available through Cooperative Extension. These programs can rapidly balance diets for protein and energy to achieve the desired body condition score, but an accurate analysis of feeds is needed to accurately balance a diet.

Table 7. Daily requirements of TDN and crude protein for a 1,200 lb mature cow.

| Stage of production | lbs of TDN | lbs of Crude Protein | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCS 4 | BCS 5 | BCS 4 | BCS 5 | |

| Late gestation | 16.0 | 12.7 | 2.1 | 1.7 |

| Early lactation | 18.4 | 15.0 | 2.9 | 2.6 |

| Adapted from National Research Council, 1996. | ||||

Table 8. Daily requirements of TDN and crude protein for a 1,000 lb first-calf heifer.

| Stage of production | lbs of TDN | lbs of Crude Protein | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCS 4 | BCS 5 | BCS 4 | BCS 5 | |

| Late gestation | 15.4 | 12.8 | 2.0 | 1.7 |

| Early lactation | 18.4 | 15.2 | 2.8 | 2.5 |

| Adapted from National Research Council, 1996. | ||||

Choosing a Supplement

A wide range of supplements can supplement existing forage to maintain or increase body condition score. Nutrients may include energy, protein, minerals and vitamins. Minerals and vitamins are not altered significantly by BCS, so supplements will be chosen based on their energy and protein concentration. Factors impacting type of supplement used will be nutrient content of forage, lactation status, desired daily gain, cost of supplement, and availability of supplement. The only way to get an accurate assessment of hay quality is to have the forage analyzed for nutrient content. Type of supplement will then be dictated by how much protein and energy supplementation is required per day to reach the desired performance level. If energy is the only limiting nutrient, most any supplement will work. High energy supplements such as corn grain will usually be the most economical. If both energy and protein are required, then a by-product with a high level of protein such as corn gluten feed, distillers grains or whole cottonseed can be used. Example supplementation protocols are shown for lactating cows in Table 9 and for dry pregnant cows in Table 10.

Table 9. Hay quality and supplementation required for 1,200 lb lactating cow producing 15 lb of milk/day.

| Quality of hay | Crude protein % | TDN % | Supplement required |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excellent | 11.2 and over | 58 and over | None |

| Good | 9.5 to 11.1 | 53 to 58 | 4 lb corn gluten feed or 3 lb corn and 1 lb soybean meal or 4.5 lb of 20% crude protein cubes or 4 lb of whole cottonseed |

| Fair to good | 8.2 to 9.5 | 50 to 53 | 6 lb of corn gluten feed or 5 lb of corn and 1.5 lb soybean meal or 7 lb of 20% crude protein cubes or 6 lb of whole cottonseed |

| Poor to fair | 7.3 to 8.2 | 50 and under | 8 lb of corn gluten feed or 6 lb of corn and 2 lb soybean meal or 8.5 lb of 20% crude protein cubes or 6 lb of cottonseed and 2 lb of corn |

| Very poor | under 7.3 | 49 and under | 9 lb of corn gluten feed or 6.5 lb of corn and 2.5 lb soybean meal or 10 lb of 20% range cube or 7 lb of whole cottonseed and 2 lb of corn gluten feed |

| Note. Recommended feeding amounts assumes cow is in a BCS of ≥ 5. | |||

Table 10. Hay quality and supplementation required for 1,200 lb dry pregnant.

| Quality of hay | Crude protein % | TDN % | Supplement required |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excellent | 11.2 and over | 56 and over | None |

| Good | 9.5 to 11.1 | 53 to 56 | None |

| Fair to good | 8.2 to 9.5 | 50 to 53 | 3 lb of corn gluten feed or 3 lb of corn or 3.5 lb of 20% crude protein cubes or 3 lb of whole cottonseed |

| Poor to fair | 7.3 to 8.2 | 50 and under | 4.5 lb of corn gluten feed or 4 lb of corn and 0.5 lb soybean meal or 5 lb of 20% crude protein cubes or 4 lb of cottonseed |

| Very poor | under 7.3 | 49 and under | 6 lb of corn gluten feed or 5 lb of corn and 1.0 lb soybean meal or 6.5 lb of 20% crude protein cubes or 5.5 lb of whole cottonseed |

| Note. Recommended feeding amounts assumes cow is in a BCS of ≥ 5. | |||

By-product feeds are an increasing source of winter supplementation in the southeast. They are often priced competitively with corn and oilseed meals. In addition, some by-product feeds have a moderate protein content, which reduces feed costs compared with a traditional corn-soybean meal mixture or a commercial protein supplement. In addition, by-product feeds such as soybean hulls, wheat middlings, corn gluten feed, distillers grains and citrus pulp are low in starch but high in digestible fiber. These by-products can be fed at higher levels than corn before forage intake and digestibility is depressed. The high starch content of corn causes a negative effect on digestion when supplementation level exceeds approximately 0.5% of body weight and worsens as supplementation level is increased. When high levels of supplement are needed, a low starch by-product feed is recommended.

Self-controlled supplements such as molasses lick tanks and hard compressed molasses or high protein blocks are popular choices because of low labor requirements. These supplements are designed to be primarily protein supplements. In most situations, cows require both supplemental protein and energy. Often, the hard block supplements cannot be consumed in great enough amounts to provide the desired level of energy. These supplements become less desirable as hay quality declines and supplement needs are increased. Additional energy may need to be supplemented when these products are fed. The liquid molasses-based supplements can be consumed at higher levels and will more closely match requirements for energy than hard pressed blocks. Consuming too much molasses, however, can cause a decrease in forage digestibility and intake.

Grazing cows on winter annual pastures is a popular choice for many producers in Georgia. Winter annual pastures are high quality, and they provide extra energy and protein for lactating cows while decreasing the feeding of hay. Winter pasture alone is too high quality for most cows; limit-grazing provides the most efficient use of these high quality forages for beef cows.

Winter pastures contain approximately 25% crude protein and 75% TDN and can meet supplemental protein and energy needs. The most popular method of grazing cows on winter pasture is limit-grazing a few hours every day. You can get satisfactory results, however, by grazing as little as every other day or just two or three days per week. Research has shown that grazing lactating cows for 7 hr per day for either two or three days per week is as effective in maintaining cow condition as grazing every day and is particularly effective for cows calving in the fall.

Economics of Supplemental Feeding

Providing supplemental feed to improve BCS for acceptable pregnancy rates is an economical practice. In almost every herd, first-calf heifers are the most difficult group to get re-bred. It has been estimated that a heifer that does not re-breed after calving costs the producer from $200 to $500. Research has shown that first-calf heifers having a BCS of 4 at breeding time will have pregnancy rates of approximately 50%, and first-calf heifers having a BCS of 5 at breeding time will have about a 90% pregnancy rate.

For example, a producer has a group of 10 heifers in a BCS of 5 at calving. If heifers are only fed poor quality hay (8% CP and 50% TDN) from calving to breeding, a decrease of one condition score is likely. The recommendation in Table 10 suggests that feeding 8 lb of corn gluten feed a day will maintain a BCS of 5. This would cost approximately $0.48 per day or $28.80 for the entire feeding period if the gluten feed was priced at $100 per ton. The producer can provide supplemental feed to these 10 heifers for 60 days prior to the start of the breeding season to maintain a BCS of 5 at breeding time.

In this example, we would expect four more heifers to become pregnant compared with no supplemental feeding. This would save $800, assuming a total of $200 for each additional heifer bred. Using an example of corn gluten feed at $100/ton, the producer can buy 8 tons of corn gluten feed with the $800 and still break even on additional feed costs. However, it would only take approximately 2.5 tons of corn gluten feed to accomplish this goal. This does not include additional benefits of higher weaning weights and earlier calving cows the next year.

Clearly, it is economical to improve body condition of lactating cows rather than reduce feed costs and have reduced pregnancy rates. Supplemental feeding must begin shortly after calving, however. Waiting until the breeding season starts is too late. Poor pregnancy rates and an extended re-breeding period is certain.

Extended Breeding Season

Some producers believe that increasing the length of the breeding season will result in high re-breeding rates of cows in poor body condition. Cows, however, will not re-breed at acceptable levels as long as they are in poor condition. This is clearly illustrated in Table 11. Cows that were in a BCS of 4 or less had only 58% pregnancy rate, despite 150 days of exposure to the bull. Cows that do become pregnant at the end of an extended breeding season will wean smaller calves and will be unlikely to re-breed the following year.

Table 11. Effect of body condition score during the breeding season on pregnancy, in terms of body condition during breeding.

| Item | 4 or less | 5 |

|---|---|---|

| Percent pregnant after 150 days | 58 | 85 |

| aAdapted from Herd and Sprott, 1986. | ||

Salvaging the Breeding Season

When cows are in condition scores of less than 5 at the start of the breeding season, increasing nutrition will improve pregnancy rates but not enough to maintain high pregnancy rates and a yearly calving interval. To achieve high (≥ 90%) pregnancy rates and maintain a yearly calving interval alternative management strategies will need to be implemented. The most effective management practice is to wean the calf to remove the demands of lactation on the cow. This management practice is often employed with first calf heifers. However, it is an effective management tool to increase re-breeding rates in mature cows.

Early Weaning

In most herds, first calf heifers usually have the lowest body condition at the beginning of the breeding season. These heifers will likely need some cessation of nursing by reduced exposure to the calf or by weaning the calf to achieve high re-breeding rates. Early weaning the calf at the initiation of the breeding season will lead to high re-breeding rates if adequate supplementation is supplied. Removing the demands of lactation greatly reduces energy and protein requirements. Early weaning must be done by the start of the breeding season to improve re-breeding rates. Calves should be a minimum of 30 days old prior to weaning.

Table 12 compares weights and condition scores of heifers with calves weaned at the start of the breeding season with those with calves weaned at the end of the breeding season. Weight and BCS at the end of the breeding season were greater for heifers with early weaned calves. Most importantly, heifers with calves weaned at the start of the breeding season had a 90% re-breeding rate versus only 50% for heifers that nursed their calf throughout the breeding season.

Another advantage to early weaning is decreased feed costs of the cow. Cows will consume approximately 20–30% less feed after early weaning compared to lactating cows and gain significantly more weight than lactating cows. Research has also shown that TDN requirements are 50% less for a dry first calf heifer to maintain equal condition scores as a lactating first calf heifer. This would represent a substantial reduction in feed costs for fall calving cows, which are fed harvested feeds through much of the lactation period. The improvements in pregnancy rates and reduced feed costs make early weaning the best option for cows that are below the desired body condition score at breeding time.

The disadvantage to early weaning is increased feed costs and management of the early weaned calf. Calves must have access to high quality winter annual pasture or should be fed a high concentrate grain mix in a drylot. Feeding programs that have used winter annual pastures plus an energy supplement have been very successful for calves weaned at less than 80 days old. Table 13 shows daily gains of early weaned calves that grazed ryegrass pasture plus 1% body weight daily of a 16% crude protein supplement. Calves were stocked at approximately four calves per acre. Weight gains were similar between the early and normal weaned calves. The winter pasture plus supplement program would work well for most cattle producers in Georgia.

Table 12. Effect of early weaning first calf heifers on weight and body condition score.a

| Item | Beginning of breeding season b | End of breeding season | Weaning c |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal weaned, wt | 941 | 919 | 982 |

| Early weaned, wtc | 907 | 954 | 1074 |

| Normal weaned, BCS | 3.88 | 4.27 | 4.50 |

| Early weaned, BCS | 3.9 | 5.11 | 6.25 |

| aAdapted from Arthington, 2002. bInitial weight was collected at the start of the breeding season. cFinal weight was collected at weaning. |

|||

Table 13. Effect of early weaning first calf heifers on calf weight.a

| Item | Early Weaned | Normal Weaned |

|---|---|---|

| Initial weight, lbb | 200 | 192 |

| Final weight, lbc | 492 | 509 |

| Daily gain, lb | 1.50 | 1.68 |

| aAdapted from Arthington, 2002. bInitial weight was collected at the start of the breeding season. cFinal weight was collected at weaning. |

||

Management Factors Affecting Body Condition Score

Several management decisions can affect the body condition of the cow herd. Some of these include stocking rate, calving season and herd health. Calving season and the duration of the calving season can influence cow body condition. Supplementation must be well planned for cows calving in the fall and early winter months, as most of the calving to re-breeding period will be on harvested feeds. In addition, a shorter calving will allow the producer to feed the herd more efficiently, because all the cows in the herd will be in the same stage of production.

Year-round calving will cause significant under- and overfeeding unless calves are managed as multiple groups. Adjust stocking rates so adequate forage is available to maintain adequate condition during the grazing season. If hay or supplement must be fed every dry spell, the stocking rate is probably too high.

Treat cattle for internal and external parasites. Georgia is an excellent environment for worms, and the cows should be treated at least once per year.

Summary

A body condition score of 5 to 6 at calving and breeding time will result in acceptable pregnancy rates. Heifers calving in body condition score of less than 5 will have less than optimal reproductive performance, even when nutrition is greatly increased after calving. Cows are more responsive to increased nutrition after calving. Clearly, it is more economical to improve body condition rather than reduce feed costs and have reduced pregnancy rates. Supplemental feeding must begin, however, shortly after calving to improve or maintain body condition. Waiting until the breeding season starts is too late to efficiently change BCS and have an impact on reproductive performance, and poor pregnancy rates will likely result. Early weaning is a proven management practice to maintain high re- breeding weights in cows and heifers calving in less than a 5 body condition score.

References

Arthington, J. D. 2002. Early Weaning – A management alternative for Florida cattle producers. University of Florida, IFAS, Florida Coop. Ext. Serv., Animal Science Dept., EDIS Publication AN131. https://animal.ifas.ufl.edu/beef_extension/bcsc/2002/pdf/arthington.pdf

Bell, D., Wettemann, R. P., Lusby, K. S., Bishop, D. K. (1990). Effects of body condition score at calving and postpartum nutrition on performance of two-year-old heifers. OSU Animal Science Research Report MP-129.

Freetly, H. C., Ferrell, C. L., & Jenkins, T. G. (2000). Timing of realimentation of mature cows that were feed-restricted during pregnancy influences calf birth weights and growth rates. J. Anim Sci., 78(11), 2790–2796. https://doi.org/10.2527/2000.78112790x

Herd, D. B, & Sprott, L. R. (1986). Body condition, nutrition and reproduction of beef cows. Texas Agricultural Extension Service. B-1526. http://agrilifecdn.tamu.edu/victoriacountyagnr/files/2010/07/Body-Condition-Nutrition-Reproduction-of-Beef-Cows.pdf

Kunkle, W. E., Sand, R. S., & Rae, D. O. (1994). Effects of body condition on productivity in beef cattle. Department of Animal Science, Florida Cooperative Extension Service, UF/IFAS. SP-144. http://ufdc.ufl.edu/IR00004528/00001

National Research Council. (1996). Nutrient requirements of beef cattle (7th ed.). Natl. Acad. Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/9791

Rae, D. O., Kunkle, W. E., Chenoweth, P. J., Sand, R. S., & Tran, T. (1993). Relationship of parity and body condition score to pregnancy rates in Florida beef cattle. Theriogenology, 39(5), 1143–1152. https://doi.org/10.1016/0093-691x(93)90013-u

Whitman, R. W. (1975). Weight change, body condition, and beef-cow reproduction [Doctoral dissertation, Colorado State University]. Mountain Scholar. https://hdl.handle.net/10217/186558

Status and Revision History

Published on Apr 14, 2006

Published on Feb 04, 2009

In Review on Jan 05, 2010

Published with Full Review on Feb 06, 2014

Unpublished/Removed on Jan 09, 2017

Published with Full Review on Feb 27, 2019

Published with Full Review on Jun 27, 2022